Unst, Shetland, Scotland

There are few places on Earth today where a sequence of oceanic rocks from the mantle to the top of the oceanic crust can be seen uplifted to the surface, but this site on Shetland has one of the most accessible and complete examples in the world.

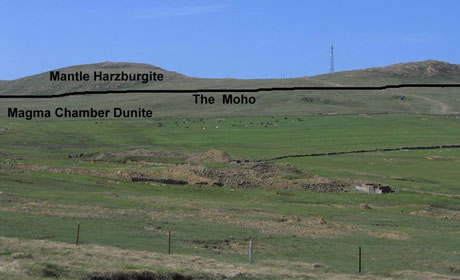

Along most of the trail that leads up to the site of the Moho you will be walking on dunite, formed in the lowest layer within the magma chamber.

Along most of the trail that leads up to the site of the Moho you will be walking on dunite, formed in the lowest layer within the magma chamber.

Dunite is made up mainly of the mineral olivine but in places it contains streaks and pods of chromite. The chromite crystallised early on as magma rose up from the mantle and so collected at the bottom of the magma chamber. Chromite is the mineral ore from which we get the metal chromium, and chromite quarrying was an important industry in Unst during the 19th Century.

The quarry at the bottom of the slope, now almost completely filled in, was once nearly 40m deep and was the largest chromite working in Britain. A highly mechanised crushing and sorting plant was in operation at the quarry and a railway carried the chromite to Baltasound for shipping. Nearby is the earlier and now restored Hagdale crushing circle.

If you continue down to the coast and follow it northwards, think of yourself as being at the bottom of the ancient magma chamber. To the north-west there are two craggy hills, the Heogs, standing much higher than the dunite. These are made of harzburgite, which was left behind in the mantle as the magma melted out. Harzburgite is made up of soft olivine and the much harder mineral orthopyroxene, and so harzburgite is harder than dunite, which is made of olivine alone. Soft rocks erode more quickly than hard ones, so the dunite forms the lower ground and harzburgite forms the hills. By looking at the shape of the land, and the variations of colour in the vegetation, you can start to ‘see’ the underlying geology.

The change from harzburgite in the Heogs to dunite marks the boundary between crust and mantle. This is the Mohorovičić discontinuity, or ‘Moho’, named after the Croatian seismologist who discovered it. Normally the Moho is many kilometres underground, but here you can walk across it!

The change from harzburgite in the Heogs to dunite marks the boundary between crust and mantle. This is the Mohorovičić discontinuity, or ‘Moho’, named after the Croatian seismologist who discovered it. Normally the Moho is many kilometres underground, but here you can walk across it!

As you head up to the road you will be walking on harzburgite. Orthopyroxene crystals give it a knobbly texture in contrast to the smoother dunite. Heading west along the boundary you can see where the two rock types mix. Moving out of the harzburgite, to the quarries and spoil heaps of Nikkavord look out for bands of hard, black chromite minerals within the orange-brown dunite.

Text: Geopark Shetland