Distinguished oil-industry geologist who later wrote two fine books for the general reader.

Michael Welland’s death from cancer in October 2017 deprived us of a versatile scientist, talented communicator, and good friend of The Geological Society.

Only child of Dennis Welland, Professor of American Literature (and later Pro Vice Chancellor) at Manchester University and Joan, a teacher, Michael was educated at Manchester Grammar School and Selwyn College, Cambridge, where he won a place in 1965. We became friends during a field trip to Arran, puffing along behind W B Harland, who shot up hillsides like a mountain goat. Harland also organized expeditions to Spitsbergen; joining one in 1967 cemented Michael’s commitment to geology.

Harvard

After graduation, he took a Masters at Harvard University, and met his wife Carol, a classicist from Mount Holyoke College. They married in 1969. The couple returned to Cambridge UK when Michael embarked on a PhD (on the geology of the eastern Othris Mountains, Greece) under Alan G Smith. Carol, working at the University Library, typed Michael’s thesis on one of the first electric typewriters, making it an unusually splendid production in the era of carbon copies.

Michael joined BGS’s Overseas Division, working in Oman (kindling his love of deserts) and publishing on the Oman ophiolite. In 1973 he took an adjunct professorship at the University of Pennsylvania before moving to Wayne State University, Detroit - researching in Nevada, and making field trips to Wyoming and Montana. He quit academe in 1977, working briefly for geothermal company Hydrosearch before joining Arco (1978 – 1992).

Dallas

The Wellands enjoyed Dallas, Michael working mostly in the south-western states; but Indonesian projects satisfied his wanderlust. He eventually became Arco’s Vice President (Exploration), but when he left, it was for three years in Indonesia, with Lasmo. Work in Algeria and the North Sea followed.

Based now in north Dorset and with the oil business in trouble, Michael quit to set up the consulting company Orogen (1997-2015). Alongside that, he took contracts in Kazakhstan, emerging chaotically from Soviet rule. Not all of them paid! Another job in Cairo (with Regal Petroleum) came to an abrupt end, in a boardroom coup. Returning to Indonesia (Atlantic Petroleum, 2011-12) was a relief.

Meanwhile, Michael nursed the idea of a book about sand. He built up an extraordinary collection of samples as he researched how vital sand was to so many industrial processes, and travelled to remote regions of the Sahara to hear the singing dunes. Sand (2009, OUP) received good reviews, containing all the arenaceous facts you could wish for, couched in an unforced, entertaining style. A documentary film (‘Sand Wars’ , dir. Denis Delestrac, 2013) followed.

Deserts

It was natural to go on to write about deserts, driven by his admiration for Ralph Alger Bagnold, who contributed so much to understanding sand’s physics. He described desert peoples, deserts’ place in history, and the creatures that live in them. The Desert: lands of lost borders (Reaktion Books) appeared in 2015.

Michael’s humour erupted into gruff laughter, particularly at the world’s absurdities. Occasionally irascible, he was never uncharitable. For him, geology always came first. His last, precious field trip was to Iceland, shortly after his diagnosis.

He is survived by Carol, children Iain and Katherine, and granddaughter Fotini.

By Richard Fortey

- A longer version of this obituary follows - Editor

Michael Welland 1946-2017

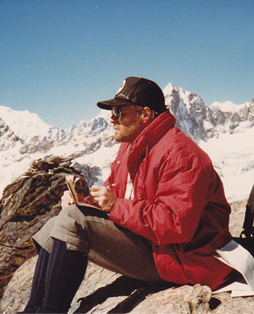

Michael Welland (pictured right, in Nepal) had a long and distinguished career in the energy industry, and then at an age when many geologists retire wrote two excellent books for the general reader infused with his deep love of fieldwork. His death from cancer in October 2017 deprives us of a versatile scientist and talented communicator, who was also a good friend of The Geological Society.

Michael was the only child of Dennis Welland, Professor of American Literature (and later Pro Vice Chancellor) at Manchester University, and his wife, Joan, a teacher. Michael was educated at Manchester Grammar School, then probably the leading school of its kind in the country. In 1965, he won a place at Selwyn College, Cambridge. I met him during the first week of geology classes, and we became friends during the indispensable ritual of the field trip to Arran, when we puffed along behind as the lecturer, W.B. Harland, shot up hillsides like a mountain goat. However, Harland also organized expeditions to Spitsbergen, and joining the Cambridge expedition there in 1967 cemented Michael’s commitment to geology. After graduation, he took the unusual route of taking a Masters degree at Harvard University, which was much harder work than staying on in Cambridge. While on the east coast of the USA he met his wife Carol, a classicist from Mount Holyoke College. Michael and Carol were married in 1969, and they remained inseparable throughout the global peregrinations that were to follow. The couple returned to Cambridge UK when Michael embarked on a PhD on the geology of the eastern Othris Mountains, Greece, under the tutelage of the brilliant and modest Alan G. Smith, to whom Michael remained devoted. In Greece he worked closely with his fellow student Andrew Hynes, another lifelong friend, who went on to enjoy a distinguished academic career at McGill University. Carol and Michael took off for their Mediterranean fieldwork in an old mini, with all the attendant mechanical misadventures. Carol worked at the University Library in Cambridge, and typed up Michael’s thesis on one of the first word processors, making the thesis an unusually splendid production in the era of carbon paper copies.

Michael’s first job was with the overseas division of the British Geological Survey, where he worked in Oman, kindling his love of desert scenery. He published a scientific paper on the structure of the ophiolite belts in the Oman Mountains. The USA soon attracted him again, and in 1973 he took a short term adjunct professorship at the University of Pennsylvania, before moving on to Wayne State University in the middle of Detroit. That city was already well past its glory days, and teaching posed particular challenges, but Michael did get to carry out research in Nevada, and made field trips to Wyoming and Montana. He decided to quit the academic career model in 1977, working briefly for the geothermal company Hydrosearch before joining Arco in 1978. He stayed with the same company until 1992, the backbone of his career. The Wellands especially enjoyed being based in Denver, but it was projects in Indonesia satisfied his hunger for travel. Michael prospered at Arco, eventually becoming a vice president of exploration in the international division, a post that allowed him to fly over the wilds of Siberia by helicopter. When he eventually left Arco it was to be based in Indonesia for three years, working for Lasmo. Michael became a star in theatrical productions of the expat community in Jakarta, while Carol amassed a huge collection of artifacts. Work in Algeria and the North Sea followed. By now, the family had a home base in rural north Dorset. In 1997 the hydrocarbon industry was in trouble, and Michael quit before the inevitable downsizing. Michael set up a consulting company – Orogen (1997-2015) – to help weather the storm.

Alongside running Orogen, Michael took on several contracts in Kazakhstan, which was emerging chaotically from the days of Soviet hegemony. A job in Cairo with Regal Petroleum got him back into the desert, but came to an abrupt end after a boardroom coup. It came as a relief to be back in Indonesia with Atlantic Petroleum in 2011-12. Through these exciting times, Michael nursed the idea of writing a book about sand. He built up an extraordinary collection of sand samples from around the world as he began to research how vital sand was to so many industrial processes. The nascent book took him to remote regions of the Sahara Desert to listen to singing dunes. When published, the book was simply entitled Sand (2009 OUP) and received good reviews. It has all the arenaceous facts you could wish for, yet retailed in an unforced and entertaining style. A successful documentary film about ‘Sand Wars’ followed (directed Denis Delestrac 2013), describing the unregulated pillaging of sand from beaches and offshore sites. It seems that this formerly commonest of materials is falling into the hands of greedy and unscrupulous people. For Michael it was a natural progression to go on to write a book about deserts – after all, he had visited many of them, and it was an excuse to claim still more. Partly his efforts were driven by profound admiration for the geologist who did so much to understand the physics of sand – Ralph Alger Bagnold. But Michael also described the peoples of these marginal lands, the geographers who got to grips with their immensity, their place in history, and the creatures that live there. The Desert: lands of lost borders was published by Reaktion Books in 2015.

Michael had a well-developed sense of humour that erupted into gruff laughter, particularly directed at the absurdities of the world, which were never in short supply. He could be irascible, but was never uncharitable. Colleagues attest to the wisdom of his advice in the unpredictable world of energy supply, but for him the geology always came first. His last, precious field trip was to Iceland, shortly after he received the diagnosis of his cancer. He is survived by Carol, his two children, Iain and Katharine, and his granddaughter, Fotini.

Richard Fortey