Philip Simon Doughty was a geologist and museologist of great distinction. At Nottingham University, he graduated in Geology, completed a Master’s degree, and helped to run the Swinnerton Geological Society. While writing his Master’s thesis on Joint densities in the Great Scar Limestone, he married Janet and taught in Keighley.

After a period as a natural history curator at Scunthorpe Museum, in 1965 he became an Assistant Keeper in the Natural History department of the Ulster Museum, Belfast. He was the first specialist geology curator to join the Museum staff in the Museum’s long and complicated history, from its origin as the Belfast Natural History & Philosophical Society Museum in 1831. It was an exciting time for the fledgling Ulster Museum – with its recent elevation from local authority to national status, growing staff numbers and a large new extension to the existing building being planned. Phil’s priority was to rescue the existing geology collections from the effects of decades of neglect.

In 1970 the Museum established a new Department of Geology, with Phil as Keeper. Against a generally favourable background of Museum expansion, over the next few years Phil and his team were responsible for creating a series of innovative and award-winning geology galleries. It is a testament to their effectiveness that, with only relatively minor changes, the displays remained popular with visitors for some three decades.

The geology collections were developed by astute purchases of display material and by systematic field collecting. The Museum’s research reputation was enhanced by collaborative projects such as the Bovedy meteorite in 1969, the 1972 Pollnagollum cave excavations in Fermanagh, and the 1986 Aghnadarragh mammoth discoveries near Lough Neagh.

Phil’s personal mission to raise the profile of geology, geology collections and museums generally, took him beyond Northern Ireland. He was a prominent member of the Museum Assistants Group, editing their newsletter, and he helped to establish the Geological Curators’ Group (GCG) in 1974. He organised a ground-breaking survey of museums for GCG, published in 1981 as The State and Status of Geology in UK Museums. This changed attitudes towards long-neglected geology collections around the country. He chaired GCG in the mid-1980s and in 2010 was awarded the group’s Brighton Medal for outstanding services to museum geology.

While a Council member of the UK Museums Association, he became involved with their Information Retrieval Group and helped to pioneer new methods of managing information about museum objects. This put the Ulster Museum at the forefront of the digital revolution in museum data handling, during the late 1970s and 80s.

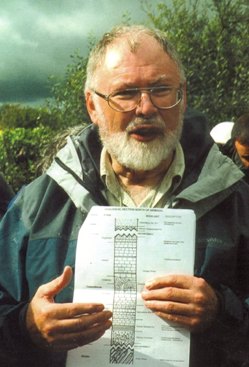

Phil was a master communicator, capable of inspiring his audience. From answering enquiries one-to-one, to the many extra-mural classes he taught for Queen’s University Belfast in the 1970s and 1980s, and establishing the Geology Tamed! lecture series at the Ulster Museum in 2002 (the year he retired), his ability to grab and hold people’s attention was clear. That same talent was evident in the field, when leading trips for the Belfast Geologists’ Society and the Belfast Naturalists’ Field Club. That ability to get the message across extended to his many radio and TV broadcasts, and to the written word – from articles in the popular press to the formality of site conservation reports – most famously perhaps, his words to UNESCO which helped bring World Heritage Site status to the Giant’s Causeway in 1986. In the Museum, the locally legendary Moon Rock display in 1970 attracted 27,000 people in a single day – which has never been beaten. The Dinosaurs Alive! exhibition in 1992 brought giant, robotic dinosaurs to Ireland for the first time, attracting 200,000 paying visitors to the normally free-admission Ulster Museum in three months – another record.

His love of fieldwork meant that site conservation and interpretation were constant threads running through his career. At the site level, he helped Fermanagh District Council with their development of Marble Arch Caves, and he was writing text for the National Trust about the Giant’s Causeway as early as 1969. At a national level, he was a founder and chairman of the Geological Society’s GeoConservation Commission. In his retirement, he wrote hundreds of ‘plain-language’ site summaries for the Northern Ireland government’s Earth Science Conservation Review (www.habitas.org.uk/escr).

He was a well-rounded scientist, with a holistic understanding of the natural world. From the early 1990s, by then Head of the Museum’s Sciences Division, he worked with colleagues in the Museum and at the Department of the Environment to nurture an infant environmental records centre that eventually became today’s Centre for Environmental Data and Recording. In the late 1990s he was a key member of the Northern Ireland Biodiversity Group, which in 2002 produced the national Biodiversity Strategy.

Phil’s professional legacy is clear – he worked and lobbied hard and successfully to improve standards of collections care and interpretation, information management, public engagement, site conservation and recording, and the development of public policy in all these areas.

He also consistently supported local and regional voluntary groups, such as the Belfast Geologists’ Society, the Belfast Naturalists’ Field Club and Earth Science Ireland – all three of which he led as president or chairman at different times.

But I suspect that Phil would have judged his most important legacy to be the countless individual sparks of interest which his infectious enthusiasm fanned into flame. For the youngster with a puzzling fossil to be identified, he could vividly bring to life a long-extinct creature from a strange and ancient world – for many, such an experience would open the door to a life-long interest in geology. What better epitaph could there be than that?

Philip Doughty was born in Wombwell, Yorkshire on 5 March 1937, died in Belfast on 14 January 2013 and is survived by three children, James, Sarah and Peter.

By Peter Crowther