Paul Maliphant, Helen Reeves, Bob Leeming and Darren Bryant revisit the Aberfan Disaster and ask – what did we learn?

A new plaque in remembrance of the former Merthyr Vale Colliery, unveiled in 2015 as part of the redevelopment of the colliery surface for housing, reads:

Merthyr Vale Colliery (formerly Taff Colliery)

1869 – 1989

Sunk by John Nixon from 1869 in Owain’s Riverside Meadow (Ynysowen) on the bank of the Afon Taff the first commercial coal was brought to the surface in 1875.

The colliery finally closed on 25th August 1989 following a long and proud existence punctuated by one of the darkest days in the history of coal mining.

The corners of our memories may be eroded and softened by time but they live on in the local communities first established to house the coal miners of the colliery and their families.

Those memories, and the lessons learned, also live on in the collective memory of ground engineering and allied professionals, and the legislative legacy of the tragedy and we would be foolish to allow the vitality of such knowledge to wane with time. As such, every opportunity should be taken to remind ourselves and the next generation of professionals what we learnt from that darkest of days.

Those memories, and the lessons learned, also live on in the collective memory of ground engineering and allied professionals, and the legislative legacy of the tragedy and we would be foolish to allow the vitality of such knowledge to wane with time. As such, every opportunity should be taken to remind ourselves and the next generation of professionals what we learnt from that darkest of days.

Picture: Memorial to the Merthyr Vale Colliery 2015. The memorial is located in the centre of the new roundabout at Bells Hill and incorporates a half sheave wheel from the old pithead, moved from the grounds of Ysgol Rhyd y Grug, and a life-size sculpture of a miner looking reflectively towards the river.

Legislation

Numerous publications, both technical and non-technical have described and discussed the causes and effects of the disaster. The most important of these publications is the Report of the Tribunal appointed to inquire into the Disaster1. Essential causes of the disaster were the inappropriate placement, tipping methods and ineffective management coupled with site conditions - all exacerbated by heavy rainfall.

Tipping began above the village in 1916 when more easily accessible sites lower in the valley became exhausted, creating seven distinct mounds by 1966. In the aftermath of the disaster most of the spoil was removed to Cnwc tip on Mynydd Merthyr and the remaining spoil at Aberfan reshaped to the current profile. Stability was improved by two drainage tunnels, to draw water from the aquifer below the tip. After re-grading, the tip was grassed and has for a long time been let for grazing under an agricultural tenancy.

Picture: New road bridge under construction, 2015, the first new crossing of this reach of the Afon Taff since 1906. Reclaimed tips, community centre and location of Pant Glas School in the background.

One of the most significant developments after the Aberfan disaster, and a requirement highlighted in the Finding XVII of the Davies Report1, was new legislation to remedy the absence of laws and regulations governing mine and quarry waste tips and spoil heaps. This aspect of mining had previously received scant attention and was scrutinised in great detail. The development of legislation activated research into the factors that could cause instability in colliery spoil tips. As a result, the Mines and Quarries (Tips) Act 1969 provided guidance for the stability of tips, and the Mines and Quarries (Tips) Regulations 1971 gave detail on construction and inspection. After the 1969 Act, the word ‘tip’ was introduced into the amended Mines and Quarries Act 1954.

The immediate effect of this was that the National Coal Board and the Welsh Development Agency invested over £50 million2 into investigations of existing tips and in improving their stability. However, the most significant outcome was that future tips were properly planned, sited and designed to ensure stability. As a result there have only been a handful of minor tip failures since, and to the knowledge of the HSE there have since been no reported injuries, let alone fatalities, caused by unstable UK tips.

This legislation stood the test of time, with no amendments and no exemptions, until both documents were replaced by the new Mines Regulations 2014, which retain the provisions relating to stability.

Disused tips

Disused tips

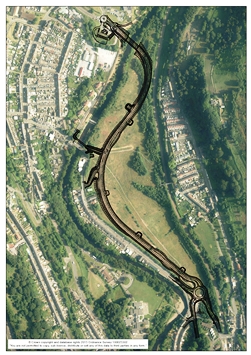

Picture: Drone’s-eye view of the new road and flood defences under construction on the former Merthyr Vale Colliery site.

The Coal Authority has decided that its own tips shall be inspected and managed to a standard not less than that required under legislation for closed tips by Regulations 17(1) and (2) and Regulation 18 of the Mines & Quarries (Tips) Regulations 1971. In practice this is very much a minimum standard and a significant proportion of the Authority’s tips are subject to a more rigorous management regime.

The Coal Authority currently owns and manages 40 disused colliery tip sites in England, Scotland and Wales (see After Coal by Richard Hughes, Geoscientist 26.03 April 2016). The Authority’s Public Safety and Subsidence Department has a management programme which includes inspections of each site on a minimum six monthly basis, with some sites inspected more frequently as required. The inspection programme includes regular walkover inspections, surveys and groundwater monitoring, and is supported by a Code of Practice that is used by other organisations as an example of best practice regarding spoil tip management.

The fundamental aspect of the management system is inspection by competent persons at a maximum interval of six months. Attention is paid to any change of situation and condition or indication of movement and to surface and subsurface drainage. The inspection interval is a matter for engineering judgement and is reduced where there are concerns for matters that might affect stability or have consequences for environmental damage.

It is Coal Authority policy to undertake a comprehensive review of each disused tip at a maximum interval of 10 years. Following at least one detailed inspection a comprehensive report is prepared commenting on all matters relevant to management and security of the tip. Reports are of the same technical standard and content as those required under Regulation 18 of the Mines & Quarries (Tips) Regulations 1971.

Ground engineering

Following the disaster of October 1966 there was also an interest in developing the applied geoscience professions in engineering geology and hydrogeology; as skills in soil mechanics and hydrogeology were highlighted in the Finding XVII of the Davies Report1. This interest contributed to the development of the first applied postgraduate Masters courses in engineering geology and hydrogeology, as well as the creation of the Engineering Geology Unit at the (British) Geological Survey3.

Following the disaster of October 1966 there was also an interest in developing the applied geoscience professions in engineering geology and hydrogeology; as skills in soil mechanics and hydrogeology were highlighted in the Finding XVII of the Davies Report1. This interest contributed to the development of the first applied postgraduate Masters courses in engineering geology and hydrogeology, as well as the creation of the Engineering Geology Unit at the (British) Geological Survey3.

Picture: Aerial view of Merthyr Vale Colliery site with new infrastructure added.

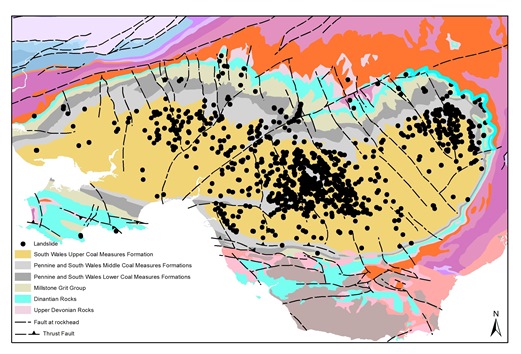

From 1976 until 1991 considerable advances in slope instability research in South Wales was undertaken (see Table), as a result of a Welsh Office initiative, and sponsored by the Department of the Environment4. These studies first centred on assessing instability on slopes (e.g. type, distribution, activity) in specific areas of concern in South Wales for land instability (e.g. Blaina, Rhondda, East Pentwyn and Bournville) and then broaden out to look at wider regions and the national scales (e.g. Great Britain, South Wales coalfield – see figure).

These studies provided better information on slope instabilities (landslides) and have aided slope management relevant to the needs of local authority planners and developers4. Further developments in slope instability assessments and modelling, documented in Siddle et al.5, highlight the improvements contributed by information technology and the application of Geographical Information Systems to aiding the communication of hazards associated with slope instability for the planning and development community in Great Britain.

Table: Government-sponsored landslide research in South Wales (after Siddle & Bentley, 2000)

|

Date

|

Research

|

Author & Date

|

|

1976

|

Causes of the instability in the area of Blaina, Ebbw Fach valley

|

Gostelow, 1977

|

|

1977-1979

|

Survey of landslides in Rhondda and north east part of the coalfield

|

Northmore et al., 1978

|

|

1979-1980

|

Survey of all landslides in the coalfield

|

Conway et al., 1980

|

|

1981-1983

|

Investigation of shallow landslides and trial landslide susceptibility maps

|

Conway et al., 1983

|

|

1983-1985

|

Ground between East Pentwyn and Bournville landslides

|

Halcrow, 1985

|

|

1984-1986

|

Development of a methodology for landslip mapping

|

Halcrow, 1986

|

|

1984-1987

|

UK review of research into landsliding in Great Britain

|

Geomorphological Services Ltd., 1987

|

|

1987-1989

|

Effects of slow moving debris slides on buildings

|

BRE, 1990

|

|

1987-1988

|

Effects of mining on hillslope stability

|

Halcrow, 1989

|

|

1988-1991

|

Monitoring trial period of using landslip potential maps

|

Halcrow, 1991

|

Picture: Simplified geology and distribution of landslides in the South Wales Coalfield

Future

In 2015, nearly 50 years after the failure of the Merthyr Vale Colliery Tip 7 and over 25 years since closure of the mine itself, communities in Aberfan and Merthyr Vale started the long journey to a more optimistic future, with the completion of new roads, flood defences and bridges as part of the residential-led regeneration of the former colliery surface in the valley floor. House-building is expected to begin in 2017, and infrastructure construction has already inspired the community to create a new scout troop and an annual Community Christmas Fayre.

The community must be allowed to move forward, supported in the hope that, in time, the name Aberfan will no longer be synonymous with the word ‘disaster’. However, geological and engineering professionals should always remember that some practice is led not just by technical knowledge but by social drivers, to ensure that events like those of October 1966 in a small, semi-rural and close-knit community in the South Wales coalfield are never repeated.

References

- Davies, H E; Harding, H; & Lawrence, V 1967. Report of the Tribunal appointed to inquire into the Disaster at Aberfan on October 21st 1966. HMSO, London. 151pp. Online version at www.nuffield.ox.ac.uk/politics/aberfan/tri.htm.

- Taylor, L E 1985. Introduction and background statement. In: Morgan, C (ed.) Proceedings of Symposium on Landslides in the South Wales Coalfield. 3-8. The Polytechnic of Wales

- Culshaw, M G; Northmore, K J; & McCann, D M 2014. A short history of engineering geology and geophysics at the British Geological Survey. In: Lollino, G, (ed.) Engineering geology for society and territory. Volume 7. Springer, 257-260.

- Siddle, H J; & Bentley, S P 2000. A brief history of landslide research in South Wales. In: Siddle, H J, Bromhead, E N, & Bassett, M G (eds.). Landslides and landslide management in South Wales 9-14. National Museum of Wales, Geological Series No.18, Cardiff.

- Siddle, H J, Bromhead, E N, & Bassett, M G (eds.) 2000. Landslides and landslide management in South Wales. National Museum of Wales, Geological Series No.18, Cardiff. 116pp

* Paul C Maliphant – Development and Projects Director, Mott MacDonald Ltd.; Helen J Reeves – Science Director Engineering Geology, British Geological Survey; JR (Bob) Leeming - HM Chief Inspector of Mines, Health and Safety Executive; Darren Bryant – Principal Project Manager (Tips), The Coal Authority.