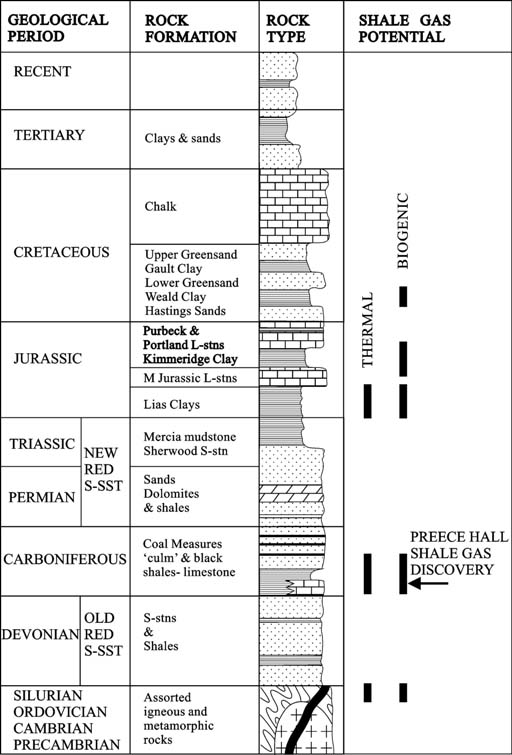

Several potential shale gas sequences were identified within the British stratigraphic column. In the early 1980s it was generally believed that shale gas could only be generated by the thermal maturation of kerogen beyond the oil window. The study concluded that PreCambrian and Lower Palaeozoic shales were generally too metamorphosed to be potential reservoirs. Most Cretaceous and younger organic-rich mudrocks were deemed too un-compacted to fracture, and too immature to generate gas. Carboniferous shales in general, and Namurian shales in particular, were thought to be ideally suited, both in terms of maturity and in the degree of natural fracturing (Figure 4). At that time, profit made by the extraction of petroleum was liable for both Corporation Tax and Petroleum Revenue Tax (introduced 1980). Shale gas production was not economic under this tax regime.

On 8 January 1985 the conclusions of the Imperial College study were presented to the UK Department of Energy. The Department expressed polite interest, but the exempting of shale gas from Petroleum Revenue Tax was a non-starter. Subsequent attempts to inform the wider world of the UK’s potential shale gas resources failed miserably. Publication was rejected by several UK journals including Nature and a certain major geological society in London. (One editor returned the manuscript opining Janus-like that the paper was too speculative and contained nothing new.) Finally however, the conclusions of the research were published in the USA

3.

WAGONS ROLL

Meanwhile, back in the USA, the US Department of Energy research set the shale gas bandwagon rolling out from the Appalachians, geographically, stratigraphically and technologically. The Appalachian basin from New York State through Ohio to Kentucky and Illinois was the main historic area for shale gas production. But there was shale gas production in other basins.

In the Williston Basin, for example, the Bakken Shale had produced gas since 1953. Stimulated by the Department of Energy and the Gas Research Institute shale gas plays were found in the Cretaceous Lewis Shale of the San Juan Basin, the Mississippian (Lower Carboniferous) Barnett Shale of the Fort Worth Basin and the Devonian Antrim Shale of the Michigan Basin. The latter play was of particular interest. Geochemical studies revealed that the gas was not thermogenic, but instead produced by bacterial methanogenesis. The bacteria had entered the fractured shale from groundwater, percolating from overlying glacial drift.

This second process for gas generation opened up new areas for exploration - areas where the source-rock was previously considered immature for thermogenic gas generation. The renaissance was enhanced by improved methods of drilling and completion. The ability to drill multiple wells from a single pad was financially and environmentally rewarding. While being able to drill not only vertically, but horizontally, and to steer the bit towards ‘sweet spots’, enabled permeable gas-charged zones to be tapped into.

Seismic techniques, which could use the fracturing process as an energy source, enabled gas charged ‘sweet spots’ to be imaged in 3D. More dramatic hydraulic and explosive fracturing techniques were developed. So there is nothing new in artificial fracturing - it has been used in the oil industry for some 60 years, and applied to hydrogeology since the days of Moses4 and Poseidon (according to the foundation myth of Athens).

NO CHANGE

Meanwhile back in the UK nothing had changed on the shale gas front. Published reviews of the future petroleum potential of the UK by staff of the Oil and Gas Directorate of the Department of Trade & Industry (successor to the Department of Energy) omitted any mention of shale gas resources. The only positive step was the repeal of the Petroleum Revenue Act (1 January 2003). The 6th Petroleum Geology Conference on the Global Perspectives of NW Europe took place at the Queen Elizabeth II Conference Centre, London, in the same year. The three-day programme concluded with a session on non-conventional petroleum. The last presentation was on the shale gas resources of the UK. There were four people in the vast auditorium: one delegate, the session chairman, the speaker and the projectionist. The presentation updated the conclusions of the earlier study of some 15 years before. It applied the advances in US shale gas exploration and production technology to the UK, in particular recognition that gas may have been generated, not only by the thermal maturation, but also by bacterial methanogenesis. New drilling and well completion techniques enabled higher initial flow rates. The presentation was published two years later 5. More publications on the UK’s shale gas potential have now followed

6 & 7.