Morgan, N., Geology from the Train. Geoscientist 30 (2), 26, 2020

https://doi.org/doi: 10.1144/geosci2020-072, Download the pdf here

Geologist and science writer Nina Morgan celebrates the advantages of going 'on line'

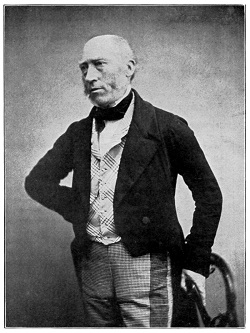

In 1835, the geologist John Phillips – among many other things, the first keeper of the Yorkshire Museum, and later first Professor of Geology at Oxford University and first keeper of the Oxford University Museum of Natural History – wrote to his sister Anne with a vivid description of his first train journey. He was travelling on a 'flying Steed of Iron' from Manchester to Liverpool.

In 1835, the geologist John Phillips – among many other things, the first keeper of the Yorkshire Museum, and later first Professor of Geology at Oxford University and first keeper of the Oxford University Museum of Natural History – wrote to his sister Anne with a vivid description of his first train journey. He was travelling on a 'flying Steed of Iron' from Manchester to Liverpool.

Phillips quickly became a convert to travel by train, even though, as he described in a letter to Anne sent from Manchester on 30 March, 1841, delays were not uncommon.

"I found the Train of yesternight very good travelling till we entered on the Leeds & Manchester line at Normanton. Then began this singular amusement: to lose time so as to arrive in 4 hours from Leeds, the time really required being 2 1/2 hours. We did this odd railway feat by stopping 5 minutes each at about 10 stations & using all possible precautions not to go too fast. This is said to be on account of the recent embankments not allowing of rapid transit..."

Sound familiar?

Best seller

Delays on the line notwithstanding, Phillips, a prolific and fluent writer, was also quick to see the potential offered by the new lines to introduce the wonders of geology, scenery and history to the travelling public at large.

Phillips's book, Railway Excursions From York, Leeds and Hull, first published in 1853, was a popular success. It went through several editions and was republished under various titles. It also inspired other geologists to jump onto the platform. As the railway network expanded throughout Britain, so did the number of authors keen to describe the geology of their part of the country from the windows of a train. The number of geologists who recognised the geological potential of the new lines also grew.

For example, in 1878 the Geologists' Association organised an excursion by train to examine the geology exposed in the cuttings being dug between Chipping Norton and Hook Norton as part of the Banbury and Cheltenham District Railway. Participants were advised to take the train from Paddington to Chipping Norton, with luggage directed to The White Hart, Chipping Norton, a journey that sadly is no longer an option.

Many others followed in their tracks, risking an addiction to train spotting in the cause of science. In 1886 Sir Edward Poulton published an account of The Geology of the Great Western Railway journey from Oxford to Reading; in the same year Edward Maule Cole published his classic book, Geology of the Hull and Barnsley Railway, complete with a fold-out coloured geological map. In 1945 the Oxford geologist W.J. Arkell published his classic paper, Geology and Prehistory from the train, Oxford to Paddington. Arkell’s methods of observation were paid tribute by Philip Powell, who added a final chapter to his 2005 book, The Geology of Oxfordshire, outlining the geology that can be seen when travelling on part of the Cotswold Line from Moreton in Marsh to Reading. Meanwhile, the geologist Eric Robinson, now retired from University College London, prepared numerous handouts for students and amateur geologists describing the geology that can be seen from trains leaving from various London stations.

Along the way all of the 'railway geologists' painted vivid pictures both of the geology and the countryside as they saw it, and their descriptions provide a valuable insight into landscapes and railway lines now lost.

Life in the fast lane

"A railway tour is life in a hurry", Phillips proclaimed in his pioneering railway book. He clearly enjoyed the rush, and so did the many other geological authors and lovers of the countryside who followed in his tracks. Even today, with a railway geology book in hand, those delays along the line can turn into a real pleasure – depending on where you get held up, of course!

End notes

This vignette is an abbreviated version of a presentation I gave at the joint conference of the Yorkshire Geological Society, University of Hull and the Hull Geological Society in March 2019 at Hull University. Thanks to Patrick Boylan and Eric Robinson for lending many of the references mentioned, and to the Director and archivist and librarian at the Oxford University Museum of Natural History for permission to quote from a letter in the John Phillips archive.

Nina Morgan is a geologist and science writer based near Oxford. Her latest book, The Geology of Oxford Gravestones, is available via www.gravestonegeology.uk