Much of the UK has experienced some form of mining in the past. Laurance Donnelly and Martin Culshaw discuss The new Abandoned Mine Workings Manual (C758D), a manual that provides a risk-based approach to the identification, evaluation, mitigation and remediation of mining hazards and their associated risks.

Legacy of mining

Civilisation today could not function, as we know it without mineral commodities. Mineral resources are fundamental and impinge on the life of most people in one form or another. Mining, probably alongside agriculture, represents one of the earliest of human activities in the United Kingdom (UK) and globally. There is evidence for the mining of minerals in the UK during Neolithic times (some 5,000 years ago), for example, at Grime’s Graves flint mine in Norfolk. The mining of metalliferous minerals, namely tin and copper, took place in parts of Devon and Cornwall in the early Bronze Age roughly 4,000 years ago. Coal mining is recorded as taking place in Northumberland in the middle of the Thirteenth Century and was probably being extracted as long ago as Roman times. However, it was the Industrial Revolution during the Eighteenth Century that led to the widespread mining of coal, iron and other minerals. This resulted in rapid urbanisation and the expansion of many of the UK’s industrial towns.

Right: Collapse of an abandoned tin mine shaft, Gunnislake, Cornwall (BGS@UKRI)

There are very few parts of the UK that have not experienced some form of mining in the past. However, mining for coal and metalliferous minerals is now much reduced and new mines are rarely opened, although there are some notable exceptions such as the recent proposals to develop a huge new polyhalite (a form of potash) mine beneath the North Yorkshire Moors. There is, however, considerable extraction of industrial minerals for aggregate and civil engineering raw materials.

New mineral extraction is strictly controlled by planning regulations to minimise the environmental effects of mining. However, the centuries of previous mineral extraction have left a legacy of abandoned quarries, pits and underground mines. One of the problems associated with mineral extraction is that while the location of quarries and pits is more obvious when extraction ceases (unless they are infilled) the locations of many of the underground mines and their access shafts and associated hazards are unknown. Indeed, it was only from 1872 that, legally, coal mine plans had to be provided when a mine became abandoned.

Left: Drilling rig being pulled form a collapsed mineshaft, Glasgow (BGS@UKRI)

Left: Drilling rig being pulled form a collapsed mineshaft, Glasgow (BGS@UKRI)

Mining in the UK has, in the past, generated vast wealth. However, notwithstanding the social impacts of mine closures, the subsequent reduction in mining and, in particular, underground mining, generated mining and environmental hazards. In extreme cases, mining disasters resulted, which have been prevalent in the past few hundreds of years. For example, the Pretoria mine explosion in 1910 killed 344 men and boys at Hulton Colliery, Westhoughton in Lancashire. The catastrophic failure of colliery spoil from Taff Merthyr Colliery at Aberfan, in South Wales, in 1966, generated a flow slide that killed 144 people including 28 adults and 116 children. In 1973, at Lofthouse Colliery, near Wakefield, Yorkshire, an inrush of water caused the deaths of seven miners. The River Fal in Cornwall suffered widespread and severe pollution in 1992, when a flooded tin mine became breached.

In the UK, for land that is located within a mining area it is essential that mining hazards are identified and the potential risks evaluated before land is developed, construction takes place or engineering infrastructure projects are proposed. The failure to properly assess the hazards and associated risks from past mining can result in the sterilisation of land or financial and engineering losses and, in relatively rare cases, loss of lives.

Guidance on Abandoned Mine Workings (SP32), Published 1984

Left: (Right) Construction over Abandoned Mine Workings (SP32), Healy & Head (1984)

To try to improve our knowledge of the hazards from abandoned mineworkings and reduce the risks, P. R. Healy and J. M. Head wrote a guidance document in 1984 called, ‘

Construction over abandoned mineworkings’ for the Construction Industry Research and Information Association (CIRIA) and the Property Services Agency (PSA) (Healy & Head 1984), also known as ‘SP32’. It was relatively short (94 pages), but it did provide the building and construction industries with some sort of a guide as to what to expect when abandoned mineworkings were encountered. It included discussion of the following:

• Methods of mining for coal, metalliferous deposits, gypsum and anhydrite, calcareous deposits, sandstone and salt.

• Surface stability in undermined areas covering abandoned bell pits, shafts and adits, pillar and stall workings and longwall workings. This was covered in only six pages.

• Site investigation of abandoned mining sites, including planning the investigation and the methods used. The two sections were covered in only eleven pages.

• Remediation and treatment of shallow abandoned mineworkings and the treatment of shafts.

• Foundations suitable for undermined areas.

SP32 also included two useful appendices on sources of information (at the time of publication) and a discussion on contracts for the consolidation of old shallow mine workings.

In the years that followed the publication of SP32 the nature of mining in the UK changed radically. SP32 alone, no longer provided a single reference document for abandoned mineworkings. There were new sources of data and information that had become available, for example, held by the Coal Authority and the British Geological Survey. There were also widespread abandoned mining hazards that occurred in the decades that followed, after the publication of SP32. These were largely attributed to the sudden demise of UK active mining, particularly coal. There was new research and cases available to document mining hazards not included in SP32. This included, for example, fault reactivation, the generation of fissures and the initiation or reactivation of landslides. Other hazards were directly attributed to the mine closures and abandonment of entire mining areas, such as mine water rebound. These were prevalent in both the former coalfields and metalliferous mining districts.

Right, Acid mine drainage, The Delph, Bridgwater Canal, Worsley, Greater Manchester (Photo: Laurance Donnelly)

Right, Acid mine drainage, The Delph, Bridgwater Canal, Worsley, Greater Manchester (Photo: Laurance Donnelly)

The gradual decline and virtual demise of the UK mining industry in the past few decades resulted in an increase in the number of abandoned mines, urbanisation and the continuous redevelopment of land in former mining areas and there was a need to produce an updated version of SP32. In the early 2000s, one of the co-authors (Laurance Donnelly) asked CIRIA whether SP32 should be reviewed and updated to provide more accurate and relevant guidance on the investigation, management and mitigation of mining hazards in the UK. In the years that followed, ‘

Mining and its impact on the environment’ (Bell & Donnelly 2006) was published, which provided an overview of the various environmental aspects of abandoned mines for development or redevelopment of former mining areas. In 2008, Laurance wrote to the Engineering Group of the Geological Society to ask, if CIRIA SP32 should be updated, something which was simultaneously being considered by The Coal Authority. The first phase and a scoping study included considerable dialogue and potential funders to support a full and comprehensive revision of CIRIA SP32.

The new Abandoned Mine Workings Manual (C758D), Published 2019

In early 2010, work began on a new document to replace SP32. This provides a more detailed guidance for the investigation and usage of land previously mined or undermined. Whereas SP32 was heavily focused on coal, the new guidance additionally includes industrial and metalliferous minerals and mining hazards. As a result, the new manual is considerably longer than its predecessor, covering the original topics more thoroughly and a whole range of new topics. It is 545 pages long and is presented in three parts, together with 44 short ‘in chapter’ case studies and eleven appended detailed case studies. The research and writing of the project report was funded by the Coal Authority, CIRIA and other key stakeholders. It was researched, written and edited over a period of approximately ten years. A multi authorship team was established together with a project steering committee comprising a team of multi-disciplinary subject matter experts including; practising engineering geologists, mining geologists, mining engineers, surveyors and researchers from Government bodies, industry, consultancy and academia.

Left, Abandoned Mine Workings Manual (C758D), Parry & Chiverrell (2019)

Left, Abandoned Mine Workings Manual (C758D), Parry & Chiverrell (2019)

The new manual does not provide prescriptive solutions but, instead, gives information to inform and empower the professional user to make informed judgements. Generally, this provides a risk-based approach to the identification, evaluation, mitigation and remediation of mining hazards and their associated risks.

The original manual was written particularly for geologists, mining engineers and civil engineers. Whilst the new manual is expected to be of interest to all these professionals, it has also been written to be of value to consultants, contractors, regulators, planners, developers, asset owners and operators, including those also engaged with or who have some responsibility for dealing with issues associated with the legacy impacts of abandoned mine workings.

The main hazards and risks traditionally associated with abandoned mine workings are as follows:

• Shallow mine workings and subsidence.

• Mine entries (shafts and adits).

• Mine gas emissions.

• Mine water discharges.

• Outbursts and groundwater contamination.

• Past methods of mine abandonment.

There are new approaches in parts of the new manual, such as a better understanding of aspects of surface stability and a considerable amount of industry good practice in the chapters on the treatment of abandoned mine entries and mineworkings. The new manual discusses a number of other hazards that were not included in the original manual:

• Mining-induced fault reactivation.

• Mine gas emissions, acid mine drainage and mine water rebound.

• Fissuring.

• Self-heating and spontaneous combustion.

• Mining-induced landslides and slope failures.

Right: Shallow, abandoned room and pillar workings for coal, West Yorkshire (Source: Donnelly 1994)

In addition, operational case examples are provided together with extensive references. The new manual contains most of the information from the original but significantly updated in the light of more recent industry experience and research over the last 30+ years, that is, post the publication of SP32. Following an introduction, the first part contains three chapters and provides an overview of past mining in the UK. Supported by regional maps, this part shows what minerals were mined, where the mining took place and how the minerals were mined. The second part comprises five chapters and provides details of the environmental impact of past mining and, in particular, how this affected the built environment. The third part of the manual has eight chapters and provides guidance on construction in mining areas and the management of land that has been, or might have been, subjected to past mining including:

• Practical guidance and good practice for the design and implementation of ground investigations.

• Methods of remediation, including new materials now available, such as geotextiles.

• Planning, legislation and regulatory aspects of land management; construction in former mining areas is also addressed to take account of major changes in planning legislation.

• Methods for the treatment of mine workings and mine entries.

• The design of foundations for infrastructure and new buildings in mining areas.

• The importance of validation and completion (or feedback) reports for the treatment of mine workings or ground improvement measures.

• Alternative uses of abandoned mines that might, in some cases, provide an asset instead of a liability.

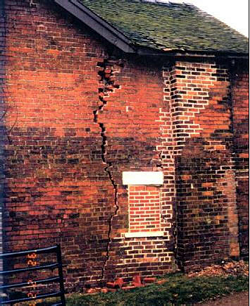

Below: Damage to houses caused by the mining-induced reactivation of the Hopton Fault, Oulton, Staffordshire, UK (Source: Donnelly 2006)

Authors

Authors

Dr Laurance Donnelly

Prof Martin Culshaw

References

Donnelly L. J. 1994. Predicting the reactivation of geological faults and rock mass discontinuities during mineral exploitation, mining subsidence and geotechnical engineering. PhD Thesis, University of Nottingham, Department of Mining Engineering.

Donnelly. L. J. 2006. A review of coal mining-induced fault reactivation in Great Britain. Quarterly Journal of Engineering Geology & Hydrogeology, 39, 5-50.

Donnelly, L. J. 2011. Ground Deformation in the Vicinity of Deep Seated Landslides in the South Wales Coalfield: Mining Induced or Geological? Geological Society of London, Engineering Group, Field Trip to South Wales, 2nd July 2011.

Bell, F. G. & Donnelly, L. J. 2006. Mining and its impact on the environment. Abingdon, UK: Taylor & Francis.

Parry, D.N. & Chiverrell, C.P. (eds). 2019. Abandoned mine workings manual, C758D. London: Construction Industry Research and Information Association (ISBN 978-0-86017-765-4).

Healy, P. R. & Head, J. M. 1984. Construction over abandoned mine workings. Special Publication 32. London: Construction Industry Research and Information Association.