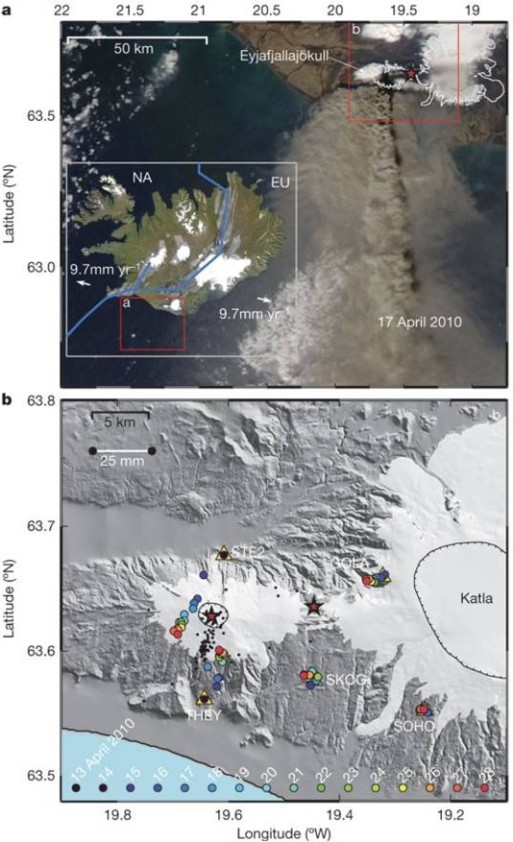

Figure 1 - A) The location of Eyjafjallajökull and the south-east volcanic zone on Iceland. NA=North American plate, EU=European plate. Average annual plate velocities shown. Satellite image shows the ash plume on April 17th, 2010. B) Displacement foci and magnitude measured using synthesis of geodetic and seismic studies. (Sigmundsson et al. 2010(vii))

Eyjafjallajökull and its icy top in 2010

Iceland is a good place to learn about volcano-ice interactions. Eyjafjallajökull is a sub-glacial volcano in the south-east arm of Iceland’s volcanic zone (Fig. 1). Its 2010 eruptions not only stopped much of Europe’s air-traffic but also brought the hazards of volcano-ice interaction and the importance of volcanology in the management of these hazards to the forefront of public and commercial attention.

About 250m of ice cover Eyjafjallajökull’s summit( ). The neighbouring larger volcano, Katla (25km to the east), is capped by the thicker Mýrdalsjökull glacier( ) (see Fig. 1). The climactic April 14th (2010) Eyjafjallajökull eruption began with effusion of basalt lava flows to the east of the summit, and it evolved into a prolonged (mid-April to mid-May) explosive eruption of intermediate (trachyandesite) magma. This followed 18 years of intermittent volcanic unrest and nearly 200 years of quiescence(vii). Critically, the “explosivity [was] amplified by magma-ice interaction,”( ) resulting in large volumes of ash.

Geodetic and seismic studies reveal that between 1994 and 2010, a complex set of four magmas accumulated at 3km and rose to 2km below the surface of Eyjafjallajökull(vii)( ). It is from these intrusions (sills) that magma broke to the surface on April 14th, 2010. Similar studies at Katla were less conclusive because the succession of sub-glacial eruptions have melted the ice cap from beneath (such as in 1999 ) and reduce the accuracy of depth estimates. The ice on Katla has historically always been dynamic, playing host to many sub-glacial eruptions that produce variable jökulhlaups and challenge hazard assessment organisations. There was no resultant eruption from Katla in 2010 and the nature of a link between Eyjafjallajökull and Katla is enigmatic, but the hazards due to volcano-ice interaction at Katla are thought to be far larger than what we saw last year from its smaller sibling(vii). It seems that ice can hinder the methods scientists employ to understand and predict what’s going on beneath.