Southern Uplands, Scotland

500 million years ago, a time where the only creatures you might recognize would be jellyfish and snails, a vast ocean existed between England and Scotland: the Iapetus. On the one side, the continent of Laurentia, a mixture of modern-day Scotland, Greenland and North America, and on the other, Avalonia, which included England, Wales and Southern Ireland. But this ocean was closing and the continents lay on different tectonic plates that were moving together. The one carrying Avalonia was being subducted beneath Laurentia. Eventually, after about 150 million years, the ocean closed up so that the two continents collided, causing what is now known as the Caledonian Orogeny (a mountain building event). The roots of these mountains are now found in the Scottish Highlands, the Lake District and North Wales.

|

|

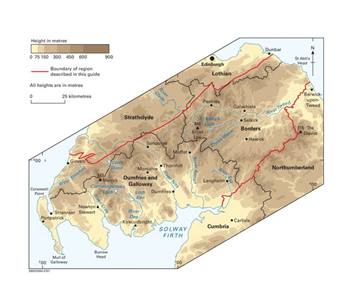

| Topographic map of the southern uplands: © British Geological Survey |

The full closure of the Iapetus took 80 million years but tectonic processes don’t stop when the lands meet. These rocks continued to be squeezed by the colliding plates and were eventually forced up and over the top of the continental plate by a series of thrust faults.

|

|

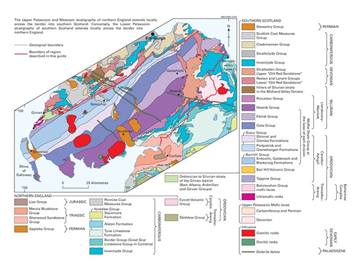

| Geology of southern Scotland: © British Geological Survey |

Today the line between Scotland, Ireland and England’s ancient continents can still be seen in parts on a Geological map, although much of it has been covered by younger sedimentary rocks. The coloured stripes that you see on a geological map of this area represent different rock types exposed at the surface, which in turn show the trend of stacked up slices of turbidites. The now fully emerged accretionary prism is also still present, it is the beautiful rolling hills of the Southern Uplands, geologically bound by the South Uplands fault in the north and the Iapetus suture in the south. Not only are the greywackes, shales and igneous emplacements still visible but one can also decipher the fault lines upon which the Southern Uplands were thrusted onto land, the power of plate tectonics still present in the rocks.

Twinned with: Nankai, Japan

As with the ancient accretionary prism formed in the Southern Uplands during the Caledonian orogeny, the Nankai accretionary prism is a product of the tectonic processes at collision plate margins. The Nankai trough marks the subduction of the Philippine Sea plate...continue reading

Related Links

- Dan McKenzie Archive

- The Rock Cycle

- Plate Tectonics schools website

- Plate Tectonics Glossary

- Caledonian Orogeny

| Back to main stories page > |

Other sites

- Twin: Windward Isles

Cwm Idwal

- Twin: Mount Pinatubo

Sperrin Mountains

- Twin: Sierra Nevada

Southern Uplands

- Twin: Nankai

Ben Arnaboll

- Twin: Glarus Thrust

Outer Isles

- Twin: Tohoku Earthquake

Clogherhead and Shannon

- Twin: Papua New Guinea

Cairngorms

- Twin: New Hampshire Granites

Great Glen Fault

- Twin: North Anatolian Fault

The Lizard

- Twin: Troodos Ophiolite

Yoredales

- Twin: Antarctica

Stanage Edge

- Twin: Ganges Delta

Hartland Quay

- Twin: Zagros Range

Amroth-Saundersfoot-Tenby

- Twin: Salt Range, Pakistan

Vale of Eden

- Twin: East African Rift Valley

Zechstein

- Twin: Sicily

Alderley Edge

- Twin: Navajo Sandstone

Isle of Skye

- Twin: Mount Kilimanjaro

Lulworth Cove

- Twin: Albania

Giant's Causeway

- Twin: Cascade du Ray Pic